Introduction to Collected Plays, I

I wrote my first play at the age of 13. The school drama group presented it to a bemused audience in the village hall belonging to the local fire brigade. To my relief, no trace of the text remains, but I have no doubt that it was abysmal. I was growing up in a peaceful, picturesque village on the Austrian border, and for a year or so I toyed with the idea of converting the upper part of our neighbor’s barn into a »theater«. The neighbor was considerably less than enthusiastic, so I dropped the idea and switched my attention to girls, which, to my suprise, brought me in touch with real drama for the first time.

I returned to playwrighting as a freshman at the University of Ljubljana, this time for radio, and won competitions for three years running. Then I grew tired of it (and of much else besides), moved first to Vienna and then to London where, at the age of 23, as a student of English literature at Chyswick Polytechnic, I wrote my first stage play, The Chestnut Crown, loosely based on my first novel A Swarm of Dust. The production of the play by the Slovene National Theater Maribor in my native Slovenia caused a stir and was, following an outcry from the moral majority, removed from the repertoire after only six performances. I didn’t care; by that time I was already in Australia, where John Bell (of the now famous Bell Shakespeare Company) produced an excellent rehearsed reading of the play at the Nimrod Theater in Sydney.

In spite of encouragement from all quarters I wrote no plays for the next twenty years (except some radio plays for the Australian Broadcasting Commision and later, back in London, for the BBC). The axis of my life had shifted to prose writing and globe-trotting, and I almost forgot that I wanted to be a playwright.

Then, in 1989, when I started to gravitate back to (soon to be independent) Slovenia, I was invited to write a play for the Slovene National Theater Maribor. The invitation came from the artistic director Vili Ravnjak, an admirer of my prose, and may have been at least partly a result of his benevolence. I wrote The Nymph Dies (the very first version, not the one printed here), and the production, though badly directed, received considerable approval. This was enough to encourage Vesna Jurca, the artistic director of The Municipal Theater of Ljubljana, to commission me to write What about Leonardo?. The resounding success of this play (full house every night, five major awards, two for the author, three for actors) and the concurrent production of Tomorrow at the Slovenian Chamber Theater (enthusiastic reviews, another major award for the author) convinced me that I was, after all, a playwright.

I had no choice but to carry on writing.

The time span separating the first and the last play in this selection (35 years) is such that any differences in style, theme and structure of the plays must be obvious. In any case I have always preferred to rely on others to tell me what my plays are about. Not because I wouldn’t know myself, but because listening to others explain one’s work can be an interesting (if not always helpful) diversion. Leaving aside the politeness one owes to people who take the trouble to pay attention to one’s work, the varied opinions always remind me of the four blind men trying to describe an elephant: to the one grabbing hold of the trunk it appears like a snake, to the next (who embraced a leg) it seems like a tree, and so on.

To some extent all opinions are valid, but naturally some are more valid than others. To be on the safe side, I tend to agree with most of them, except with the evidently stupid, shallow or malicious ones. So I have no trouble in accepting the views that Tomorrow is »a play about the birth of the postmodern society,« or that What about Leonardo? deals with the question »of personal identity in a world in which big stories eat little ones,« or that The Nymph Dies is about »deconstructing the myth od romantic love,« or that Uncle from America is »a metaphor for our eternal imprisonment in a maze of dreams, illusions and longings,« or that The Eleventh Planet is a play about »a conscious utopia as a temporary means of survival which nevertheless works, and is real,« or that Nora Nora is an »up-to-date report on the state of the batttle between the sexes.«

from Nora, Nora

If I were asked to point out one important aspect of my plays that hasn’t been highlighted, at least not before the Austrian production of Nora Nora, I would mention the meditation Nora 2 practises (during marital sex) in Nora Nora: Seize the emptiness. Most, if not all, of my central characters are deeply marked by the feeling of emptiness that permeates their efforts and the world around them. By the feeling that nothing in life is ultimately worth the trouble, except for one reason: because it’s not worth the trouble, and so—in the absence of an alternative—we might as well get on with it.

However, the thematic landscape of my plays is hardly as bleak as this makes it appear. The emptiness that my characters »seize«, each at the end of his or her Passion, lies on the threshold of the very revelation they seek; it gives them an opportunity to make peace with their conscience, for breaking out of the ring of futile wasting of energy and coming to terms with what cannot be avoided—not because of destiny but because it is an imperative of their inner logic. They make their escape by surrendering to the inevitable: Janek in The Chestnut Crown by accepting responsibility for a crime he did not commit (but of which he feels guilty), Mishkin in Tomorrow by accepting the arbitrary and whimsical nature of his surroundings (and fate), Tristan and Iseult by acccepting the death of love as the only guarantee that it may one day be reborn, Johnny in Uncle from America by realizing that he has allowed his youthful dreams to turn into the solid walls of loneliness, the three vagrants in The Eleventh Planet by accepting the painted leg of lamb (and rocket) as utopian yet somehow liberating alternative to reality, and the four love combatants in Nora Nora by realizing that the way to greater permanence in relationships between the sexes leads through an acknowledgment of and friendship with the same sex.

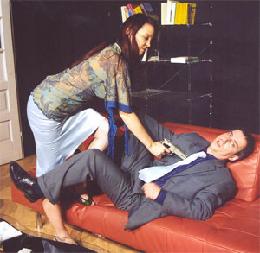

scene from Tomorrow

I have often been asked if I think that modern plays should be socially relevant. Here I am in danger of becoming rather dogged, but never mind. It so happens that the individual in conflict with society interests me less than the individual at odds with himself, with his own values, ideas, emotions. I am convinced that most misunderstandings are born first and foremost in the confusion of our convictions, desires and expectations. I am interested in the violence that we visit upon each other because of our fixed ideas, ambitions, and notions of what is “right.” Sociology has always struck me as a deficient science precisely because it deals with statistics and neglects the uniqueness of each individual, his psychological, spiritual, intimate world.

Far from being a New-Age freak, I nevertheless believe that it is impossible to improve society with political will or with social action alone. We have to start with the transformation of individual consciousness. This is not mysticism, as many would claim: this is a practical, almost utilitarian, perspec tive. Society as a system cannot surpass the moral maturity of the individuals that comprise it. Therefore, as a playwright, I am interested first of all in the individual and his or her personal “truth,” in his or her unique “story,” and how it unfolds, or runs aground, through relationships with others. Only then does my interest turn to the wider social picture, and to general human conflicts and misun derstandings. If I were pressed to find a common theme in my plays, I would probably say that they all deal with the human need to achieve the unachiev able. I agree with O’Neill that the true purpose of dramatic writing is to show the human struggle for the meaning of life.

I love and hate my characters to an equal degree; they comprise the best and the worst of me (and the best and the worst of most people I know). My characters, not all, but probably most of them, are dissatisfied with things as they are. They tend to shift away from reality to the comfort of imaginary, alternative worlds in which they can be what they want to be. Another characteristic is their paranoia, their fear that they are being followed by someone or something that will reveal and make public their most intimate secrets, their weaknesses, and expose them to the mockery of the world. That is why they are constantly fleeing from one role to another, constantly trying not to be what they fear they are. Role-playing is in their blood. They may not even realize that they’re playing roles. Of course, these plays within plays sometimes serve a different purpose, most obviously in What about Leonardo?, where I wanted to show the narrowness of the divide between “reality” and “imagination,” and how deeply our fictions affect our everyday lives.

scene from What About Leonardo?

Critics, on the whole, have been kind to me, perhaps too kind, especially those who keep patting me on the shoulder for witty dialogue, puns, reversals, double meanings, elegant con versational “sparring,” and the like. I think that these elements, although present (they must be, for how else could they have been noticed), do not represent the most important aspect of my plays. I would respectfully suggest that perhaps the essential ingredient is the underlying current of pain—bitter, gnawing pain that makes people laugh, and then, in the end, makes them shudder. It is for this reason that some critics whose kindness has remained rather lukewarm have really misunderstood my intentions. Perhaps I will not be forgiven for saying this, but Slovenians on the whole do not have a balanced attitude toward pathos and humor, intellect and emotion, tragedy and comedy. Generally we are inclined toward mor bid sentimentality, poetic expression, moralizing. Our tradition does not possess dramatic texts in which comic and tragic elements fuse or complement one another. For the Slovenian mind, therefore, tragi comedy is a sort of paradox, most resisted by literary theorists—which is an even greater paradox.

But the theater-going public has little difficulty responding to tragicomic plays. The reason, I think, is laughter releases us from the burdensome duty of treating the events on stage "deeply and seriously.” That means we can follow the play with our defences deactivated. When in this state we encounter some thing tragic, it comes as a shock, as an emotional blow—which is how it should be.

Of course my sense of humor is not pure comedy. It is black; it can be blacker than black. I would call it the laughter of desperation. It can be uncomfortable, but it penetrates deeply and is, I believe, more effective than the laughter of farce or plain buffoonery. It allows us to face the truths from which we might otherwise turn away. Isn’t one of the functions of drama making us face unpleasant truths about ourselves?

The question may have more than one answer, and my »yes« may not be as firm as I would wish, but for the time being I will stick with it because I cannot think of a better alternative.