Final Innocence

from Collected Plays II

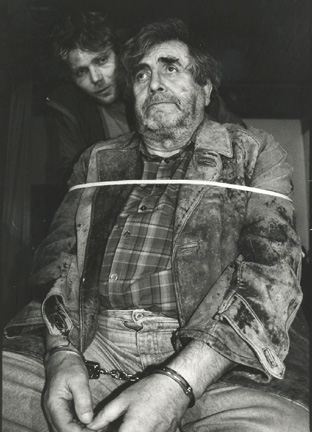

Final Innocence, Slovenian Chamber Theatre, Ljubljana, 1997

Praise for Final Innocence

A Drama of the Tragic Flaw in Christian Morality

At a time when the end of the 20th century is close and the world is looking to the future with uncertainty, the need for a collective moral and historical “stocktaking” is not only timely, but also inevitable, particularly in Europe, the most “civilized” of continents. After it had exported Christianity to “less civilized” parts of the world, created an amazing intellectual and cultural heritage, and developed sophisticated social structures and democracy, along with the tradition of charity and liberalism, in the 20th century it became the setting for the destructive Great War, the shame and the horror of the Holocaust, and the extreme savagery of the recent wars in the Balkans.

If we put to one side the socio-economic and political causes of such conflicts, we are left with the enormous burden of unresolved moral dilemmas, which in a time of collective crisis glitter with the treacherous luster of ambiguity. Final Innocence looks into this dark side of our morality. In this play, set in the final days of the Bosnian war (in which “God became a Balkan warrior”), Evald Flisar bravely takes on the foundations of our moral code, exploring the nature of personal identity, moral purity and freedom of choice. Like all good dramatists, Flisar deals with his material at a deeply human level, but reaches past the contradictions of his characters to the very heart of Christian morality, revealing its central, tragic flaw.

Final Innocence, Slovenian Chamber Theatre, Ljubljana, 1997

Each of the three characters in the play tries to repair a terrible wrong (“sin”) and to solve through positive action (“faith,” “charity,” “justice”) his own crisis and achieve salvation (“absolution”). Believers or not, they have in common the principles of charity, benevolence, compassion, as well as justice and retribution (principles that we have taken from the Old and New Testaments, and which are an integral part of our collective awareness). In short, all three speak the same moral language.

The story of three strangers who seek absolution in the heart of a living hell presents to us the drama of Christianity: one of sin, sacrifice and forgiveness. When the characters seek a way through the ruins of their wounded souls, they realize that it is possible for the roles of destroyer and victim to quickly change, and that forgiveness and sacrifice are just words in a world gone mad. Each of them gets to the point where his own suffering releases him from responsibility for the pain of others and where their shared moral language becomes dysfunctional. Because they have different syntaxes available to them, they are compelled to recreate the ruined logic of their moral code, but in doing so manage to create only a grotesque imitation. By dealing with their ordeals they also reach a point without hope where absolution in the Christian sense is impossible.

And yet the gloomy finale is not entirely without hope, as it points the possibility of a different, more courageous principle: the principle of personal, individual responsibility.

—Sladjana Vujović

Evald Flisar (1945, Slovenia). Novelist, short story writer, playwright, essayist, editor. Studied comparative literature in Ljubljana, English literature in London, psychology in Australia. Globe-trotter (travelled in more than 80 countries), underground train driver in Sydney, Australia, editor of (among other things) an encyclopaedia of science and invention in London, author of short stories and radio plays for the BBC, president of the Slovene Writers’ Association (1995 – 2002), since 1998 editor of the oldest Slovenian literary journal Sodobnost (Contemporary Review). Author of eleven novels (six short-listed for kresnik, the Slovenian “Booker”), two collections of short stories, three travelogues (regarded as the best of Slovenian travel writing), two books for children and teenagers (shortlisted for Best Children’s Book Award) and thirteen stage plays (six nominated for Best Play of the Year Award, twice won the award). Winner of the Prešeren Foundation Prize, the highest state award for prose and drama. Various works, especially short stories and plays, translated into 32 languages, among them Bengali, Hindi, Malay, Nepali, Indonesian, Turkish, Greek, Japanese, Chinese, Arabic, Polish, Czech, Albanian, Lithuanian, Icelandic, Russian, Italian, Spanish etc. Stage plays regularly performed all over the world, most recently in Austria, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Nepal, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Bulgaria and Belarus. Attended more than 50 literary readings and festivals on all continents. Lived abroad for 20 years (three years in Australia, 17 years in London). Since 1990, resident in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

|

|